When I escorted a group of students from the London School of Fashion to last year’s Années Folles exhibition in the Parisian Musée Galliéra, I had them smell some of the fragrances of the era: Lanvin My Sin, Jean Patou Cocktail, Shalimar, N°5… and Chanel Cuir de Russie. To my surprise, most of them (19/20 year-old Americans) preferred the latter despite its animalic facets, though they tend to wear the ubiquitous fruity florals of the generation… Was it by comparison, because some of the other fragrances smelled of “old lady-ish” aldehydes? Because “leather” gave them a point of reference, as opposed to the other, more abstract compositions? Or was it transference, because they had correctly guessed that their lecturer loved Cuir de Russie above all the others?

If there was only one for me, Chanel Cuir de Russie would probably be it.

Its warm, slightly oily, tarry base notes of styrax, birch tar and castoreum, which discreetly recall the most luxurious of leathers, are punctured by the aldehydic fizz; these thousands of pinpricks infuse the iris into the leather notes, to open up and dry up the composition. When the iris rises up again, propelled by the aldehydes, it carries all the other floral notes with it: jasmine, rose, ylang-ylang, orange blossom…

That’s the genius of the composition. Cuir de Russie (1924) isn’t the first fragrance of the family – it was already a genre in and of itself since Guerlain’s and Rimmel’s 1875 launch of their own “cuir de Russie”… It isn’t even the first feminine leather fragrance: Caron had been selling Tabac Blond, an oriental version of the theme, to women since 1919.

But it is a very peculiar version of the genre, because of the strong dose of iris – according to Luca Turin, this is more of a leathery iris than a leather fragrance as such. The very structure of the scent (as in Bois des Iles and N°22) is a variation of that of N°5 – which already displays a slightly leathery base, especially perceptible in the vintage versions.

Thus, Chanel Cuir de Russie is first and foremost a distinctly Chanel/Beaux aldehydic floral with a leather base, rather than a true “cuir de Russie” like, say, L.T. Piver’s.

When Gabrielle Chanel decided to add it to her catalogue, it wasn’t just because the “cuir de Russie” scents were fashionable (her collection did comprise a Jasmin, a Rose and a Chypre, all compulsory references for perfume houses at the time). During the post-WWI years, White Russians flowed to Paris, intensifying a yen for all things Russian that had already been awakened by Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Chanel herself was surrounded by Russians, starting with her perfumer Ernest Beaux; she was friends with the impresario Diaghilev, the composer Igor Stravinsky, the dancer Serge Lifar; between 1920 and 1923, she had an affair with the Grand Duke Dimitri, who was probably the one who introduced her to Ernest Beaux, a perfumer at the Imperial Court for the Russian house of Rallet.

Russia inspired her collections during that period. She borrowed the peasant blouse; she worked with furs; her fabrics were adorned with Slavic motifs by the embroidery house founded by Dimitri’s own sister, the Grand Duchess Maria.

Leather was also a scent of the zeitgeist. As a material, it was traditionally associated with masculine pursuits (cars, aviation, travel, English club chairs), the very activities the 1920s Garçonnes appropriated: as a note, it became the olfactory emblem of the emancipation of women.

The house of Chanel was keenly aware of this: a 1936 text, possibly handed out to salesladies and found by Richard Stamelman, who quotes it at length in Perfume : Joy, Obsession, Scandal, Sin, makes this crystal-clear:

“It is the very scent of travel, of the transatlantic cabin, of the hotel room where she closes sumptuous suitcases, her heart filled with the vigorous joy of promising discoveries and rich tomorrows. And this is why I easily imagine this perfume floating in the wake of a tall, slender brunette, whose moves are confident, whose voice is accustomed to giving orders, and whose fingers are slightly darkened by tobacco. She is one of those women who always wears a suit, even at midnight at the Savoy…”

In the same period, an ad, also quoted by Stamelman, warns that “well-bred ladies [will find] its scent improper”…

Today, Cuir de Russie is probably a little less animalic than in its original version: the castoreum used, if any, is no longer the Russian variety with its birch tar facets (Russian beavers eat birch), but rather the Canadian stuff (Canuck beavers feed on conifers).

But it is still an invitation to travel – travel in a bygone era of Hermès trunks and luxuriously upholstered cars rushing to Saint-Petersburg… An era for which even 20 year-old American students can yearn. But it remains as modern as a leather jacket slipped over a little black dress – which, to me, feels like home.

Chanel Cuir de Russie is now available solely in 200 ml eau de toilette bottles, in the Exclusifs collection. Despite rumors to the contrary, the parfum is still sold in 30 ml bottles in both of Chanel’s Parisian boutiques. Though the parfum most fully expresses the beauty of the composition, the eau de toilette is also excellent and well worth the price.

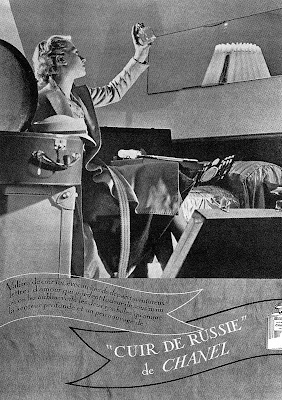

Image: Chanel 1922 “Russian” model from Vogue (document kindly forwarded by Octavian Sever Coifan of 1000fragrances from his own archives).